June 2023

Rio Mesa Banding Station. June 2023.

Rio Mesa Banding Station. June 2023.

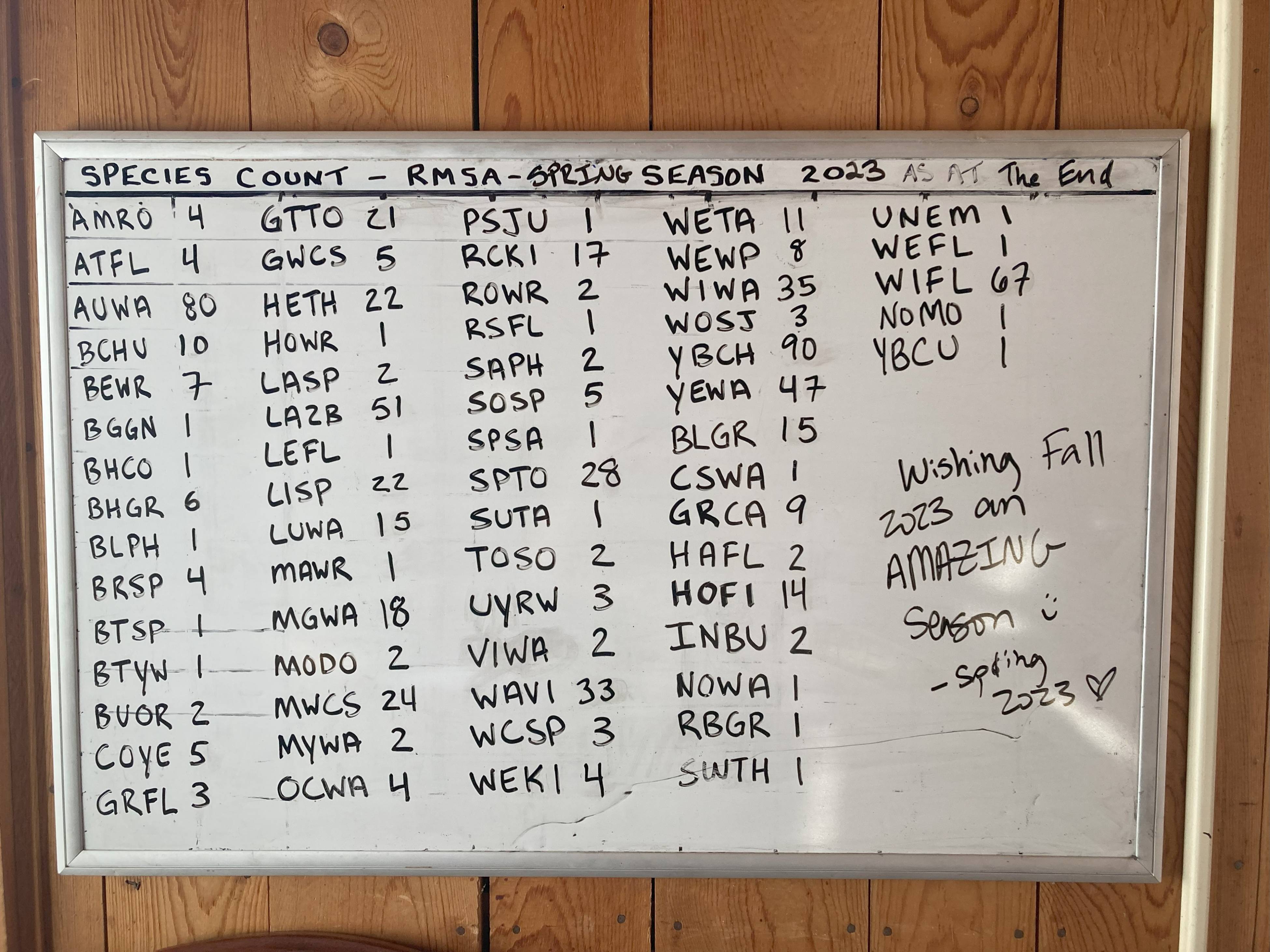

Spring 2023 species count. Alpha Codes.

Spring 2023 species count. Alpha Codes.

Green-tailed Towhee. Photo credit: Carly Crow, lead bander for spring 2023.

Green-tailed Towhee. Photo credit: Carly Crow, lead bander for spring 2023.

Further Reading

Bonderman Field Station Annual Banding Summaries

Fall bird migration in western North America during a period of heightened wildfire activity

Research ties worsening wildfires to bird mortalities

The days grow longer and hotter.

As summer ripens, the temperatures at the field station climb into the triple digits. Flows on the Dolores River drop dramatically–from spring peak flows of 7500 cfs (cubic feet per second) to 1500 cfs by the end of June. Biting flies replace biting midges. Penstemon go to seed, while beeplants bloom. The San Juan onions, whose purple-white flowers once carpeted the floor of the roadside scrub, are now brown and brittle.

June marks the start of the quiet season here at the field station. Student groups grow fewer, the songs of spring mating fade, and our migratory tenants–both human and nonhuman–move on. Among those departing the field station at this time of year are the bird banders. Each spring, they spend two months netting, examining, and banding birds along the Dolores River. Their stay spans the length of spring bird migration, when billions of North American birds make the epic journey north from their wintering grounds to their breeding grounds. To study these birds, one lead bander and two volunteers move into Deck House each year in early April, just in time for the arrival of the first avian migrants, and depart in early June, after the final wave of stragglers passes through.

Migration is an arduous affair. From as far south as Patagonia to as far north as Alaska’s Arctic Circle, two thirds of North American bird species travel hundreds, if not thousands, of miles every spring and fall over the course of weeks. Time is perilously tight. To arrive at their breeding grounds in environmental conditions favorable for nesting, birds must make lengthy flights with few breaks, fasting for much of the journey and pushing the upper limits of survival. Stopover sites along the way can mean the difference between life and death for these migrants. Birds with flight paths through the Intermountain West often depend on riparian areas, where food and shelter is more plentiful, to rest and replenish their fat stores. Bonderman Field Station at Rio Mesa, which adjoins the Dolores River, provides critical habitat for these species, making it an ideal landscape for studying the behavior and health of migratory birds.

Established in 2011, the banding station at Rio Mesa is the longest-running in Utah. The station includes an array of sixteen mist nets, whose delicate mesh is fine enough to catch small songbirds, and a covered hut where bird captures are studied. Each day, a half hour before dawn, the banders open these nets for six hours, walking net lines every thirty minutes. If they find birds, the banders carefully extract them, a practice that requires considerable skill, efficiency, and–in tangled or combative cases–a cool head. The banders place each capture in a cotton drawstring bag, which helps keep them warm, dry, and calm, while they wait their turn for study.

Birds are fragile creatures, and their safety is of the utmost importance in this process. Bird bones are easily broken; too much noise will cause them physical stress; and time in the sun can quickly overheat their small bodies. Given these risks, banders take a number of precautions and closely follow guidelines for ethical handling. Using specific grips and techniques to prevent injury, banders manage each bird gently and quietly over as short a time period as possible. If there are strong winds, rainstorms, or temperatures over 85 degrees, the banding station is closed for the day. If a bird is showing substantial signs of stress, such as losing a lot of feathers, then it is released immediately. Data collection is always a secondary responsibility to the health of the birds under study.

With these concerns in mind, the banders examine each capture as quickly and accurately as possible following MAPS (Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship) protocol. They record measurements on weight and wing size, assess fat composition on the bird’s breast, inspect flight feather plumage coloration and wear, and look for signs of breeding: in females, a brood patch, and in males, a cloacal protuberance. These observations help the banders assess not only the age, sex, and species of each bird, but also their physical condition during migration–whether their journey has been particularly harrowing or the local ecosystem is providing sufficient calories, for instance.

After making these assessments, the banders then use a set of pliers to place a well-fitted aluminum band on the bird’s leg. Issued by the United States Geological Survey, these bands include the banding location and an identification number that is unique to each bird, allowing researchers to track individuals. Since 2011, biologists at Rio Mesa have banded 15,670 birds from 122 different species. 3,383 of those birds were banded recaptures, making it possible to plot the movement and health of those individuals over time.

Once a bird is banded and ready to be released, the banders take two tail feathers and a few body feathers and place them in envelopes. Some will be sent to the University of Utah, where researchers will conduct stable isotope analyses, using heavy hydrogen isotopes to trace birds' geographic origins. Others are destined for Colorado State University’s Bird Genoscape Project. Using the DNA from collected feathers, the Bird Genoscape Project will sequence of the genome of each individual, allowing biologists to measure genetic diversity, determine the distinct populations that exist within species, and track the movement of birds from wintering to breeding sites.

For Kyle Kittelberger, a fourth-year PhD student at the University of Utah, Rio Mesa's long-term dataset is a veritable goldmine for ornithologists. Working in the Biodiversity and Conservation Lab under Dr. Cagan Şekercioğlu, Kyle manages banding research at Rio Mesa, using the information gathered here to identify trends in bird behavior, physiology, reproductive success, and survivorship. Among Kyle’s many questions about the field station’s avian residents, he is curious about how anthropogenic factors, such as climate change and habitat loss, might be impacting bird communities: Is a changing climate encouraging birds to shift their arrival and departure dates during spring and fall migration? Are birds evolving to have a lower body mass and longer wingspan to reach breeding grounds more quickly and efficiently? Do hotter and drier conditions increase concentrations of birds along riparian corridors? What about population recovery from mass bird mortality events related to large wildfires?

Kyle says that Rio Mesa is an ideal place for pursuing these kinds of questions. As a riparian corridor in an arid environment, the Dolores River offers biologists the opportunity to study critical bird habitat in a sensitive ecosystem. Stopover sites in desert environments are also surprisingly understudied, and given the realities of a hotter and drier future in the American West, the data collected here is integral to our understanding of bird migration in stressful environmental conditions. Kyle compares the data he collects here with data gathered at the Şekercioğlu Lab’s banding station in eastern Turkey, a site located on the Aras River in an arid steppe environment. If similar patterns are found at both sites, they can be a reliable indicator of global trends in bird populations.

One of the trends that biologists have identified in recent years is that migratory bird species are arriving at their spring nesting grounds earlier than they used to in an attempt to keep pace with a warming climate. By the end of the 21st century, scientists project that spring will begin nearly a month earlier than historic conditions. Despite physiological and behavioral adaptations, many bird species will likely struggle to keep up with these accelerating changes. The result is what scientists call a “phenological mismatch” with potentially catastrophic consequences for North American bird populations, which have already declined by a third since the 1970s.

Phenology is the study of biotic life cycles and their timing in relation to changes in weather and climate. The term comes from the Greek word phaino, meaning “to show, to appear, or to bring to light,” and captures the seasonality of life on Earth–the synchronization of annual variations in sunlight, temperature, and precipitation with life events, such as blooming and breeding. Humans have recorded phenological observations for millenia (the earliest known records are found in Chinese literature from 1000 BCE), using knowledge of seasonal plant growth and animal behavior to hunt and farm effectively. Phenological research helps us understand the relationship between our atmosphere and biosphere, and the behavior of species in ecological communities adapted to specific seasonal patterns.

Phenological shifts due to accelerated climate change can have serious ripple effects, throwing biotic activities out of sync with seasonal conditions, and impacting species’ ability to interact, subsist, and reproduce. At Rio Mesa, the first avian migrants in spring arrive with the emergence of insects on the landscape. If warmer temperatures drive insect hatches to peak and decline before those birds arrive, there will be little for them to eat. Likewise, early onset springs followed by unexpected cold snaps, as well as hotter and drier late-spring conditions, can damage vegetation, reducing the availability of forage and shelter. Migratory birds also face increasingly unpredictable and severe storm systems that can throw them off course and deplete their limited energy stores, making migration that much more stressful and dangerous.

This spring, our banding team handled a total of 739 individuals across 65 species, making this season the second highest on record for bird diversity. Among those birds, the banders encountered a critically endangered subspecies of the Yellow-billed Cuckoo–a first for Rio Mesa. Yellow-billed Cuckoos are long-distance migrants that winter in South America and summer in the United States. While common in the eastern half of the country, this bird has largely disappeared from parts of the west, where much of their riparian habitat has been converted to farmland and housing. Despite the challenges of migration and regional habitat loss, the individual found at Rio Mesa appeared healthy with a brood patch (an area of featherless skin on a bird's belly) that indicated she had a nest nearby. Perhaps this field station, fringed with willows and cottonwood trees, is a refuge for her and her young.

The cuckoo’s presence here reminds us that we desperately need more places that can protect and support biological diversity amidst changing environmental realities. As key ecological indicators, birds’ health reflects the health of the ecosystems they inhabit. The data collected at the banding station at Rio Mesa informs not only bird conservation measures, but also landscape-wide strategies for the restoration of wider ecological communities. Here at the field station, that means supporting research that builds the resilience of sensitive desert ecosystems, so they can support a diversity of life long into the future.

Taylor Cunningham, Staff